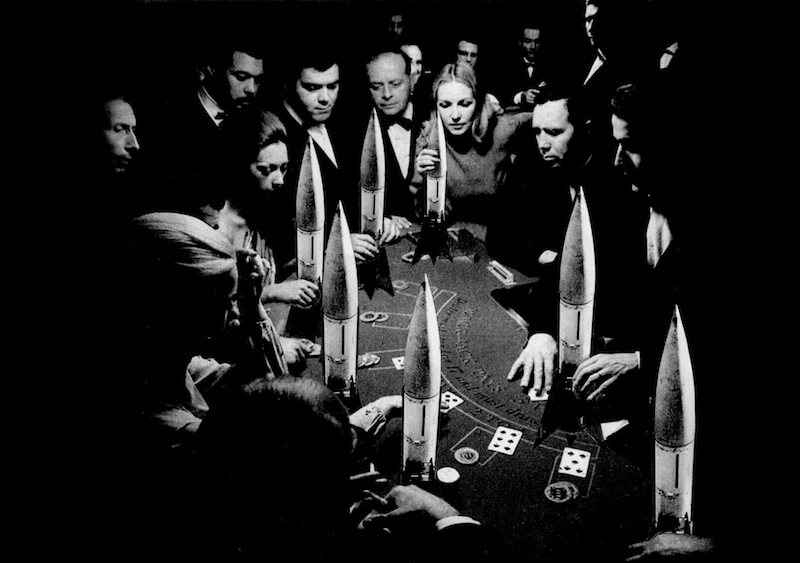

The Gamble by Peter Kennard, 1985. Silver bromide on cardboard. Collection: A/Political

The longer one looks at Peter Kennard’s photomontage The Gamble, the more disquieting it becomes. The gamblers inhabit a world of darkness and disassociation. They could be politicians, arms dealers or warmongers. They are focused with alarming self-absorption on their sinister game. Several of the group, both men and women, touch the sleek instruments of destruction with gestures that are appreciative, tender or sensual. The scene is like an informal, private-party version of the tenebrous war room in Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, an elite chamber where the bargaining chips are missiles, issues of life and death—always other people’s—will be decided, and the stakes are frighteningly high.

No matter how ingenious the illusion, it isn’t the aim of photomontage to try to kid the viewer into believing that what it shows literally exists. A photomontage is a proposition or argument, a provocative idea, and the disruptive, Brechtian cut lines are meant to register, not melt away. The medium takes facets of familiar reality and rearranges them to expose something that might otherwise remain hidden or inadequately perceived. Operating in the tradition of political photomontage that grew from John Heartfield’s scathing satirical opposition to the Nazis, there is every reason to be brutally direct. No one could mistake the righteous anger and polemical purpose in a montage by Kennard that shows a huge fist snapping a nuke in two.

The Gamble is a subtler, slower-burning kind of image. It leads us to think about the clandestine operations of power and the mentality of those who presume to wield it for annihilatory ends. The original artwork, closer to square in shape than the version shown here, can be seen in the retrospective exhibition “Peter Kennard: Unofficial War Artist,” which opened last week at the Imperial War Museum in London. Based on a photograph of a casino found in an American magazine, the montage was always intended to be a mobile, activist image, disseminated in print rather than hung up for sale on a gallery wall. It was first published in 1986 in About Turn: The Alternative Use of Defence Workers’ Skills (Pluto Press) and it has made other appearances over the years. Kennard used it in 2013 in a series of downloadable protest posters targeted at the G8 summit of wealthy countries held in the UK.

In the exhibition catalogue, he prints the montage again, as a full-page bleed, stamped with the figure 17,270—the number of nuclear weapons known to exist in 2013. The cabal of missile lovers in the shadows is still doing a roaring trade.See all Exposure columns