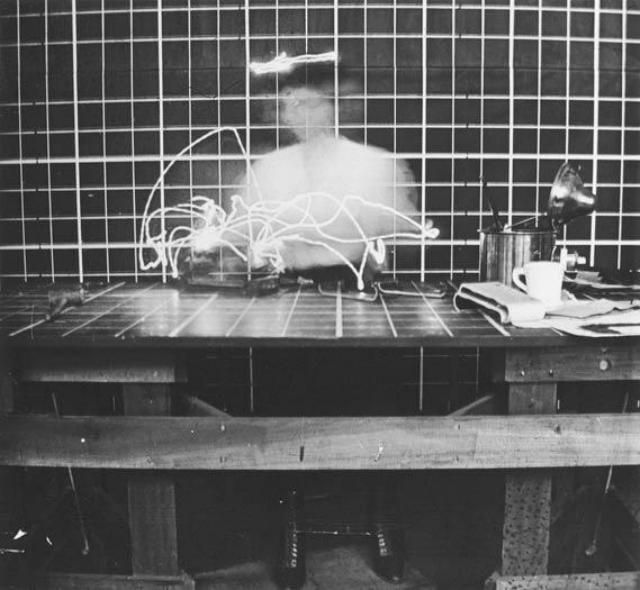

Motion efficiency study by Frank Gilbreth, c. 1914. Collection: National Museum of American History

This ghostly image reappeared to me by chance while I was clearing out my office, where the black-and-white press picture was buried in a pile of papers. The photo from around 1914 featured in a documentary series titled The Big Company shown on Britain’s Channel 4 in the late 1980s. I didn’t keep the print because I was especially interested in time-and-motion studies, though this is what it shows. What appealed to me then, and this hasn’t changed nearly three decades later, is the combination of the spectral figure of the woman—her boots under the table are the most solid thing about her—and the grids behind her and covering the tabletop. The set-up almost certainly reminded me of the gridded platform in Peter Greenaway’s film A Zed & Two Noughts (1985), where dead animals, including a crocodile, are filmed in the process of decay.

My print is even stranger in one respect than the tonally more accurate version I am showing here. In my copy, the woman’s body is entirely white and her face has completely disappeared. With the darkening of the print, however, the two faces on either side of her head can be seen more clearly, as though they are peering in at the animated apparition through the back of a cage. These faces are, in fact, her own, multiply exposed on the film. A small light bulb is attached to her head, and the camera’s open shutter captures her movements, traced by the squiggle of light floating above her like a squashed halo. She carries similar bulbs on her hands so that her actions, as she carries out an unspecified manual task, can be recorded and analyzed.

As so often with scientific and technical photographs, an image produced purely for research purposes can take on the ambiguous character of art when viewed out of context, and artists such as Picasso would later play with the possibilities of painting with light. For the picture’s author, Frank Bunker Gilbreth (1868-1924), a pioneering management consultant, the aim of these cyclegraphs, as they were named, was simply to improve the efficiency of repetitive tasks, though time-and-motion studies were often unpopular with workers, who feared being reduced to robotic mechanisms, and sometimes refused to cooperate with researchers. Gilbreth and his wife and professional partner Lillian, an industrial psychologist, were more compassionate in their thinking than some other exponents of scientific management. One humane outcome of rationalizing factory workers’ performance might be to reduce needless fatigue. Nevertheless, the erasure of the phantom woman’s identity within this hard-edged chamber of grids still looks like an unintentional warning of the dehumanizing pressure of the relentlessly monitored production line.