All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace, written and directed by Adam Curtis, BBC, 2011

In 1967, the American novelist and poet Richard Brautigan published a poem titled “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace.” This is also the perfectly chosen title of a three-part documentary by Adam Curtis — a true maverick of the airwaves — that started screening this week in the UK. Keenly anticipated, the program has been generating a tremendous buzz. It’s a complex, demanding, uncompromising and visually audacious piece of television. I have watched the first episode twice and will probably watch it again. Will it be shown in the US? I hope so. The entire program is about America. It couldn’t be more relevant.

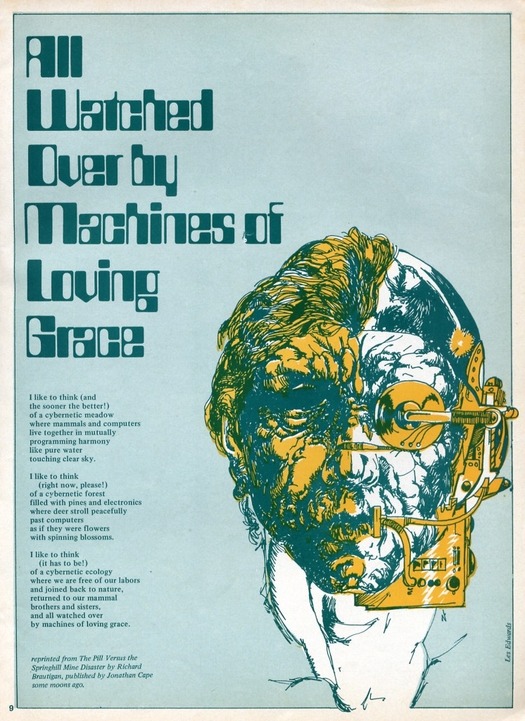

In his poem, Brautigan pictures a world where “mammals and computers live together in mutually programming harmony” and “deer stroll peacefully past computers” in cybernetic forests, as if these marvelous machines were “flowers with spinning blossoms.” In this electronic paradise, we will be delivered from our labors and freed to return to nature, while our benevolent cybernetic stewards tenderly take care of our needs. For Brautigan, this psychedelic vision of a blissed-out, countercultural technotopia couldn’t arrive soon enough, and his poem was certainly prophetic. The social revolutionaries of the 1960s became the equally certain, equally visionary digital entrepreneurs and gurus of Silicon Valley. “This generation absolutely swallowed computers whole,” Stewart Brand, founder of the Whole Earth Catalog, told a magazine in 1985, “just like dope.”

Page from Oz no. 34, April 1971. Poem by Richard Brautigan. Illustration by Les Edwards

Curtis’s argument in All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace is grippingly summarized in a three-minute trailer on his blog for the BBC. (If this doesn’t work outside the UK, the trailer is also available with a profile of Curtis here.) In this transcription, I’m following the division of phrases he uses in capitals on screen, superimposed on a collage of images from archives, news stories and films:

We live in a dream world created by the machines

Where we are all connected

And we are all free

Even in love

But the machines brought with them another idea

That we are all components in systems

Nodes in a global network

We dreamed the systems could stabilise themselves

Through feedback

And create a perfect balance

In nature’s ecosystems

And in human society

And in capitalism

Without politics and the old hierarchies of power

But power hasn’t gone away

It never does

This is the soundbite version of the program’s thesis. The first episode, Love and Power, constructs an intricate, hour-long historical argument that takes in Ayn Rand (seen in a 1959 TV interview — weird and utterly fascinating); members of her circle, including Alan Greenspan, later head of the US Federal Reserve; Rand’s novels The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged, by the early 1990s the second most influential book in the US after the Bible; Silicon Valley hotshots who saw themselves as Randian colossi and named their companies and kids after the author; Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky; and Robert Rubin, banker, Secretary of the US Treasury, and then a banker again.

The cybernetic utopians believed that if you could link people by machines they would create their own kind of order, making government control and regulation unnecessary. When Clinton arrived in office, eager to begin expensive social reforms, as he had promised, Greenspan informed him that the deficit was already too large. He must cut spending and then interest rates would go down and the market would boom. It would be the markets, monitored by international computer networks able to supply instantaneous feedback, that would transform the US, not political intervention. This they certainly did, but Greenspan was worried because productivity hadn’t increased, so where, in that case, was all the money coming from? When he tried to raise the alarm, the political outcry forced him to back down. He concluded — erroneously — that in this “new economy” there must be new forms of productivity that his data somehow didn’t register.

A summary of just one sequence in the program comes nowhere near to doing justice to its investigative methods. Curtis moves from slow exposition and observation to passages of deliriously fast cutting. He is a brilliantly subtle editor with an exceptional feeling for music. Over the Greenspan story, he lays “Monkey 23” by The Kills, creating a sensation that everything is running down. “A sense of lethargy and quietness came over the Whitehouse,” Curtis then observes (he always voices his own films). “It was as if the President didn’t have anything to do.” In the next sequence, he uses Leonard Cohen’s “Suzanne” over a slow-motion scene where Lewinsky gazes into Clinton’s unseen face with a look of rapturous longing, during a meeting with him in a crowd (“And you want to travel with her/And you want to travel blind/And you know that she will trust you . . .”).

And so the story continues, through Clinton’s distraction and departure; the failure of economies in the Far East; the body blow of 9/11 and the sense that everything would change only to find it didn’t; the Chinese Politburo’s economic cunning; the new false boom that followed in the West, and the inevitable crash, until we reach a conclusion that’s all too familiar now. The utopian cybernetic dream was for a new kind of global governance, stable market democracy and “planetary consciousness.” The computers were supposed to liberate us from political control, making us Randian heroes in charge of our own destinies. But exactly the opposite has come about. “We are helpless components,” says Curtis at the end of the first episode, “in a global system, a system that is controlled by a rigid logic that we are powerless to challenge or to change.”

Machines of Loving Grace is not easy viewing in content or form. Some might find Curtis’s melancholy conclusions (so much for Brautigan’s “mutually programming harmony”) too much to take. I prefer to see this in terms of the famous saying attributed to the political thinker Antonio Gramsci. We need to apply “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.” Cultural and political criticism of this kind — incredible to find it survives on TV — attempts to inform, outrage and radicalize the audience because without clear understanding and emotional engagement, there can be no fighting back. Curtis is a kind of Jan van Toorn of the moving image — Van Toorn often said that the designer, too, should be a reporter — and designers could learn a great deal from studying this masterly documentarist’s techniques of building an integrated argument with image, sound and text.

Curtis’s work is harder to see than it should be. Machines of Loving Grace is available on iPlayer, but not outside the UK — there are ways around this. The BBC has yet to release official versions of earlier series such as The Century of the Self (2002), The Power of Nightmares (2004) and The Trap (2007). (It might be an intractable rights problem; all the films use vast amounts of old footage.) Unofficial versions are available from Amazon, but image and sound are said to be poor. In the US, the video magazine Wholphin released The Power of Nightmares with issues 2 to 4 on separate discs. These appear to have been withdrawn, according to the McSweeney’s Store, also for rights reasons.

Thankfully, Curtis has made It Felt Like a Kiss available on his blog. This 54-minute film was part of an installation/performance staged with a theater company in Manchester in 2009. It’s an electrifying, often deeply disturbing piece of work that shows Doris Day, Rock Hudson, Saddam Hussein, the CIA, and Enos, the first chimp launched into orbit, in a startling new light.