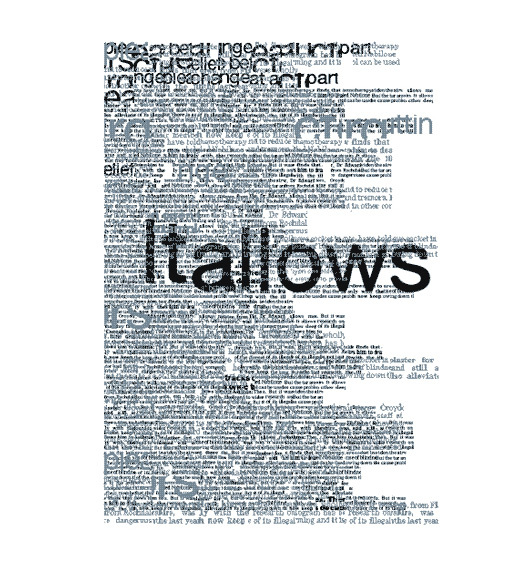

Poster by Neville Brody

In a response to Michael Bierut's essay, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mentor, Or, Why Modernist Designers Are Superior, Andy Chen questions the rules of modernism, examining why we need to look beyond the -isms.

I’ve often asked myself why graphic design so seldom reflects or delivers deeply emotional experiences in the way that music, theater, or film can. Part of it, I think, results from modernism's pervasive influence and insistence on neutrality — the removal of the visible presence of the designer's hand and a belief in clarity, restraint and order. In his recent essay on modernism, Michael Bierut notes that the search for these attributes requires rigor, humility and a respect for craft. However, so-called “rules” that demand a modular grid or prescribe a palette of “authorized typefaces” define the boundaries and character of communication. While modernist designers refine this approach with an attention to appropriateness and ambiguity, their belief in a “universal” form puts constraints on expression. This is particularly evident in typography, where gestures that inject a sense of personality — extreme tracking or leading, vertical or horizontal scaling, stacking of letterforms — are considered “crimes.” While it's true that design is a problem-solving mechanism, and not a vacuum for self-expression, I wonder if our work could benefit from a more personal tack.

Discipline is not the same as repression, and personality is not the same as indulgence. After all, Massimo Vignelli's work is full of his personality: it’s austere, restrained, and dignified. But reifying his beliefs as a universal set of rules limits our ability to express the full gamut of human experiences and emotions. Sure, the type is in a grid, it's perfectly legible and it's carefully laid out. But does that mean that I want to read it? Or that it successfully honors its content in the most appropriate way? Bierut notes that readers might “react with horror” at his submissiveness to Vignelli's rules, but the message is actually quite conservative: learn the rules before you break them. I appreciate Bierut's injunction to “fuck them up a little,” but who gets to decide these rules, and why? No design device is implicitly right or wrong; typography, color and composition produce emotional effects that can be calibrated to serve content while preserving personality.

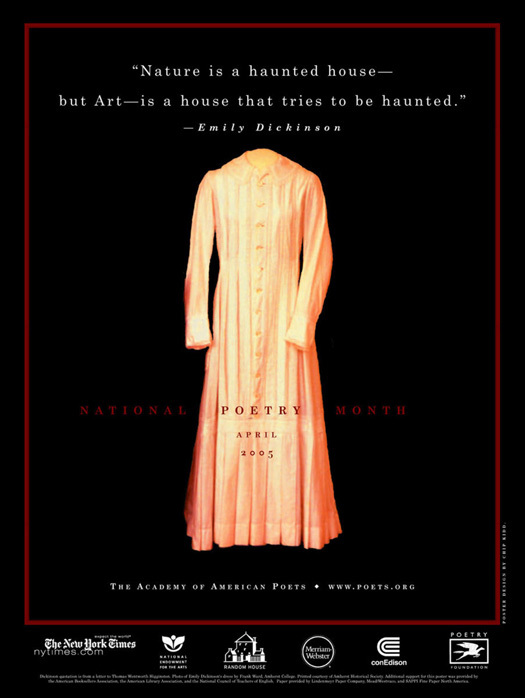

Chip Kidd, National Poetry Month poster, 2005

This review of Chip Kidd’s poster for the 2005 National Poetry Month is a case in point: the reviewer praises Kidd’s design only to disparage his use of lowercase letterspacing as a self-indulgent distraction. The poster features Emily Dickinson's dress floating in a field of black below a line of her poetry: “Nature is a haunted house — but Art — is a house that tries to be haunted.” Kidd's letterspacing does not distract from meaning; it modulates it. Like the treatment of the image, the spacing helps create the sense of haunting indicated by the quote. The air between the letters suffuses the words with feeling. The choice is conceptual, and not merely stylistic. This willingness to look beyond -isms and rules, treating devices from multiple design traditions as fair game, typifies Kidd's approach. The repeated use of lowercase letterspacing across many of his covers represents a sustained exploration of this device and its contribution to visual cohesion, emotional resonance and concept.

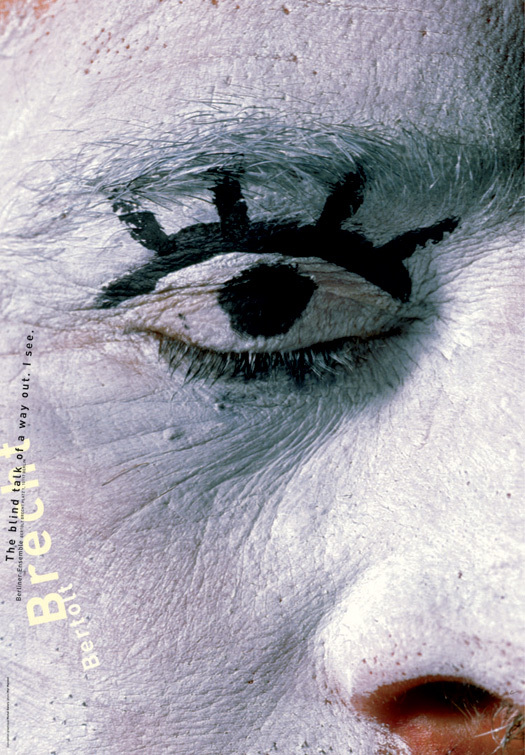

Michal Batory, Bertolt Brecht exhibition, 1997

Respect for a tradition is not the same as unquestioning fidelity to it. On this point, Bierut and I would seem to agree. Some of the most emotionally-resonant graphic design manages to borrow qualities from modernist philosophy without slavishness to its formal dictates or a loss of personal touch. In a poster for an exhibition on Brecht by the Berliner Ensemble, Michal Batory uses a single, tightly-framed image of a mime’s eye to illustrate a carefully chosen line of poetry: “The blind talk of a way out. I see.” The eye is closed, but an open eye is painted over it. Typographically, Batory uses wide letterspacing and a painterly arrangement to contrast the dense photo with a sense of weightless flow. The resulting composition is surreal and irreducible — beyond formal prescriptions and the desire to break them.

Neville Brody, Spread from the Anti Design Festival guide, 2010

Last summer, I had the opportunity to work with British designer Neville Brody on the inaugural Anti Design Festival. Clearly, the festival was meant to incite controversy and make a case for anarchy and disruption. I was never completely comfortable with this stance, but working with Neville helped me come to terms with it. Watching him design the festival's materials was both shocking and inspiring. He would throw design elements onto the page with an improvisational flair, bending and twisting them to his will. He would use big type with leading so tight that the ascenders and descenders would clash, shift type sizes and faces in the middle of a sentence, and value type for the way it felt as much as for what it said. What resulted was a fearless graphic language that gave voice to schizophrenia, failure, anger and frustration. Disordered as it was, Neville's design had a logic all its own: one filled with as much humanity and mastery as Vignelli's oeuvre. Towards the end of the summer, he asked me why I was going to graduate school. Innocently, I responded that I hadn't been educated in graphic design, and that I needed to learn the ground rules to become part of the profession. He grinned at me wryly and said, “Andy, there are no rules. You have to make your own rules.”