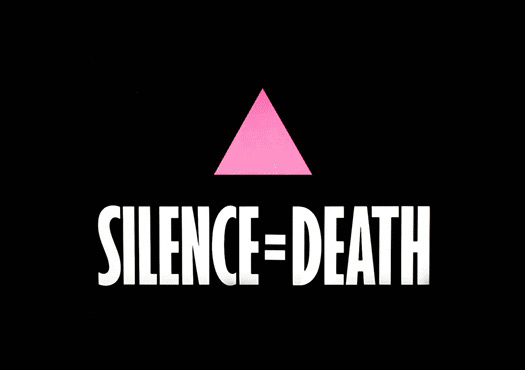

Silence = Death from ACT UP

In the last several years, the LGBT movement has made significant strides: same-sex marriage is now legal in five states and the District of Columbia. And earlier this month, Federal Judge Virginia Phillips issued an injunction banning the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy that has prevented gays from serving openly in the military.

Despite these advances, homosexuality is still portrayed as something alien or pathological to mainstream sexuality. This “otherness” is the basis on which discriminatory attitudes are built and sustained and where designers play a significant role in engaging the struggle for LGBT rights.

The stigma surrounding LGBT status is intricately tied to its pathologized history: it wasn’t until 1973 that the American Psychiatric Association declassified homosexuality as a mental disorder. Nevertheless, the movement for LGBT rights has remained deeply connected to the history of the AIDS epidemic. Originally referred to as GRID (Gay-related immune deficiency) or the “gay plague,” AIDS was thought to be transmitted exclusively through homosexual contact and was characterized as punishment for sexual promiscuity. [1][2] This “serves them right” mentality led to the design of slogans like “AIDS Kills Fags Dead” (a play on the bug spray tagline “RAID Kills Bugs Dead”) and “AIDS Cures Fags.”

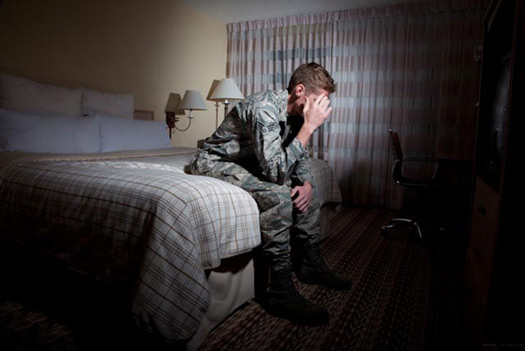

Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell by Jeff Sheng

Activists faced a daunting task: they had to dispel homophobic misperceptions surrounding AIDS as a “gay disease” while coping with the reality that the epidemic seemed to disproportionally affect men who had sex with men. [3] The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) decided to confront this challenge head-on and invented the tagline “SILENCE = DEATH” set in stark white type on a solid black background. They cleverly adopted the pink triangle — a downward-pointing version once used by the Nazis to identify homosexuals in the concentration camps — and turned it upright, taking a symbol of shame and discrimination and reclaiming it to represent the fight for survival.

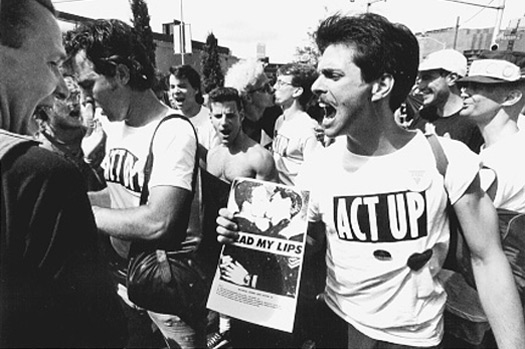

In a single breath, the “SILENCE = DEATH” campaign enjoined LGBT people to speak out about their sexuality and release themselves from the shame of getting tested for HIV. By registering mainstream anxieties about the connection between “gay” and “plague,” ACT UP used graphic design to attack stigma by exposing it. According to sociologist Joshua Gamson, this mentality galvanized activists into staging raucous, theatrical kiss-ins that usurped public spaces — like baseball games and cocktail parties — commonly considered the domain of middle America: “ACT UP here seizes control of symbols that traditionally exclude gay people or render them invisible and take them over, endowing them with messages about AIDS; they reclaim them, as they do the pink triangle and make them mean differently. In doing so, they attempt to expose the system of domination from which they reclaim meanings and implicate the entire system in the spread of AIDS.” [4] ACT UP’s campaign put the onus on LGBT people to speak out fiercely and engage with participatory democracy as a matter of life and death, effectively linking individual accountability with social activism in the battle against disease.

ACT UP Archival Photo

In recent years, much of the urgency surrounding HIV/AIDS activism has waned. Anti-retroviral therapies have been successful at confronting the virus, and as a result, HIV is no longer regarded as the death sentence it once was. The prevailing view today is that protection against sexually-transmitted infections is a matter of how you have sex and not whom you have it with.

This relaxing of attitudes, however, is not uncomplicated. According to a recent report by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), people who self-identify as “men who have sex with men” (MSM) continue to be the cohort most severely affected by HIV, accounting for more than half of all new infections in the United States.[5] While the incidence of HIV has declined among the general population since the 1990’s, the rate of new infection has steadily increased in the MSM population, especially among the youngest age group (13-29). The CDC posits that the MSM population is particularly at risk because of a lack of knowledge about HIV issues, complacency about risk and fear of social discrimination. Especially among the younger population, who did not experience the illness and death indicative of the early AIDS epidemic, HIV is not a serious reality. Younger gay men are less likely to speak openly about their HIV status and more likely to make false assumptions about their partners’ status. Many participate in “serosorting,” or having sex with people they believe to be of the same HIV status.

For my generation, the “SILENCE = DEATH” design is relatively meaningless. On a superficial level, we simply don’t believe that AIDS will kill us or that our proclivity for disease is affected by our degree of “out-ness.” On a deeper level, a campaign couched in the bifurcated language of outrage, on the one hand — and the fear of death, on the other — has less significance for younger LGBT people. Though it is arguably easier to come out than it ever has been, those who are still uncomfortable committing to the “gay” label are unlikely to align themselves with the proposition that their silence is inherently self-destructive. Strangely enough, the very slogans and symbols that once empowered a generation of activists have now become effete and even self-stigmatizing.

Still from Fall From Grace by K. Ryan Jones

In part, this has to do with the disease-prevention premise of slogans like “SILENCE = DEATH” or “Don’t Die of Ignorance.” While powerful at the time they were produced, designs aimed at using fear and shame to compel at-risk audiences to be tested for HIV/AIDS now only redouble stigma. Many LGBT people are already afraid of playing into society’s beliefs about the “unnaturalness” of their sexual orientation and would sooner silence themselves than admit to participation in risk behaviors.

To successfully address these issues, we should not merely aim to prevent disease; we should strive to promote health — that is, the right to a fulfilling, satisfying life free of stigma and shame. The visual language we use to confront HIV/AIDS should empower people to choose lives that are consistent with their own ideals and not merely lecture them to use condoms. On a broader level, this approach invites people to participate in defining what health is on their own terms, as opposed to forcing them to restrict that understanding to the terror and dread of disease.

This is not to say, however, that we should fail to register the sense of loss that accompanies the onset of HIV. Sunny, optimistic campaigns like LIVESTRONG might succeed in raising money for cancer research, but they often fail to provoke real awareness for the struggles that survivors, their families and the bereaved face on a daily basis. The branding approach has a tendency to reduce the complexities of disease to a colorful fashion accessory, emotionally detaching audiences from the stakes of inaction. Particularly with a disease so complexly intertwined with issues of sexual orientation, a wristband or ribbon doesn’t cut it.

Instead, we need to recognize the specific challenges the LGBT population faces, while couching those challenges in a broader, empathic narrative about the universal desire for health. As an example, our designs could tell the stories of young LGBT people who are living with HIV — living on their own terms and not dying on somebody else’s. Instead of emphasizing the link between silence and death, we should draw a connection between openness and life. Being tested for HIV and asking about HIV status before sex should be regarded as an essential part of this openness.

In addition, we need to provide a basis from which non-LGBT people can relate to these stories by making the case that every person living with HIV/AIDS — gay or not — is somebody’s son or daughter and deserves an equal measure of respect and dignity. Broadly speaking, we need to portray LGBT people as part of the collective human tapestry rather than external to it. We need to put a stop to the “us against them” mentality that has typified the thinking behind the previous generation’s design solutions: instead of trying to reclaim words like “queer” in attempts at resistance, we need to get mainstream society to see LGBT people as “human.” Instead of staging kiss-ins intended to elicit feelings of disgust among the heteronormative mainstream, we should strive to create a condition where two men kissing in public is just as acceptable as a man and woman kissing. Social dissent is not more powerful simply because it aims to antagonize.

Vigil for Matthew Shepard. Photo by Reuters

To be clear, I am not arguing that we should diminish the individual ways in which LGBT people express their sexuality or abandon the impulse to speak out against discrimination and homophobia. Matthew Shepard was tortured, beaten, and hung on a fence to die because he was gay; it is our responsibility to keep his story alive. But in a world where the “unnaturalness” of the LGBT population is still used as an excuse to withhold otherwise inalienable rights, we can and need to do better.

Rather than pitting LGBT rights against mainstream values, we need to celebrate the individuality of LGBT people within the context of the rest of the population. Even as we focus on individual cases of intolerance to illustrate specific experiences with homophobia, we need to connect the dots and show how discrimination damages our values as a society. Otherwise, our laws might very well change, but ignorance and bigotry will remain.

A graduate of Princeton University, Andy Chen recently completed a Fulbright Scholarship at the Royal College of Art Helen Hamlyn Centre in London, where he researched sexual health outreach to older adults. He is currently a graduate student in Graphic Design at RISD.

Notes

1. Helene Joffe, “Social representations of AIDS: towards encompassing issues of power.” Papers on social representations, 4.1 (1995): 1-2.

2. Peter Conrad, “The Social Meaning of AIDS,” in Ray C. Rist, Policy Issues for the 1990’s, (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1989), 78-79.

3. Joshua Gamson, “Silence, Death, and the Invisible Enemy: AIDS Activism and Social Movement ‘Newness’,” in Michael Burawoy et. al., Ethnography Unbound (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), 39-41.

4. Gamson, 46.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (March 2010). “HIV and AIDS among Gay and Bisexual Men.” Available from http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/FastFacts-MSM-FINAL508COMP.pdf

1. Helene Joffe, “Social representations of AIDS: towards encompassing issues of power.” Papers on social representations, 4.1 (1995): 1-2.

2. Peter Conrad, “The Social Meaning of AIDS,” in Ray C. Rist, Policy Issues for the 1990’s, (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1989), 78-79.

3. Joshua Gamson, “Silence, Death, and the Invisible Enemy: AIDS Activism and Social Movement ‘Newness’,” in Michael Burawoy et. al., Ethnography Unbound (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), 39-41.

4. Gamson, 46.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (March 2010). “HIV and AIDS among Gay and Bisexual Men.” Available from http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/FastFacts-MSM-FINAL508COMP.pdf