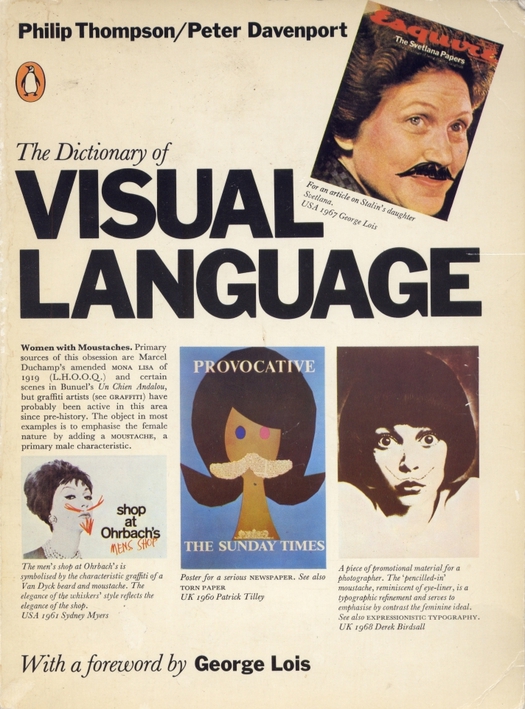

The Dictionary of Visual Language, written and designed by Philip Thompson and Peter Davenport, Penguin, 1982

I have contributed a list of 20 books every graphic designer should read to Steve Kroeter’s Designers & Books website, which is rapidly growing into a wonderful resource. There is also an interview with me about books on the Designers & Books blog.

One of the titles I have chosen is The Dictionary of Visual Language. The text that follows below is a short piece I wrote about this design classic for the “Archive” feature in Eye no. 11 in 1993 — my opinion of the book, which was first published in 1980, remains as high as ever. I wrote about the dictionary again in a recent essay titled “Love of Lexicons” in Eye no. 78, winter 2010. It’s good to see that Angus Hyland of Pentagram, whose book list is online today, has also selected the dictionary for Designers & Books.

Philip Thompson and Peter Davenport’s original title for the book was “The Dictionary of Graphic Clichés,” until they bowed to their publisher’s request for something that sounded more positive. In some ways this was a pity because, as Thompson argues in his introduction, the effectively redeemed cliché is, historically, the very crux of graphic communication, and it is the “international and trans-cultural acceptance of the visual cliché that is its greatest virtue.” First published by Bergstrom and Boyle, the book has been out of print in Britain since the Penguin edition of 1982. It deserves immediate reissue because its analytical method is unique.

“Graphic design is a language,” writes Thompson. “Like other languages it has a vocabulary, grammar, syntax, rhetoric.” To demonstrate this thesis the authors assemble a huge array of visual examples under an alphabetical sequence of subject headings: barrel, basket, bath, bayonet, beach . . . feather, fence, fig leaf, figurehead, file . . . mousetrap, moustache, mouth, mug shot. The effect is to make the reader see familiar material drawn from four decades of graphic design from a largely unfamiliar angle: not as the portfolio masterpieces of individual designers, but as part of the broader stock of visual culture in which we all share.

The dictionary also serves as a sobering reminder of how much graphic design has changed in the last decade. It is not that the visual language it explores so thoroughly has disappeared, since clichés by their nature will persist, but these devices come now with a great deal more graphic and typographic paraphernalia attached. They are less central — which is probably what older designers mean when they repeatedly bemoan the dearth of “ideas.”

See also:

An article about making book lists. Plus, an earlier design (and visual culture) book list.