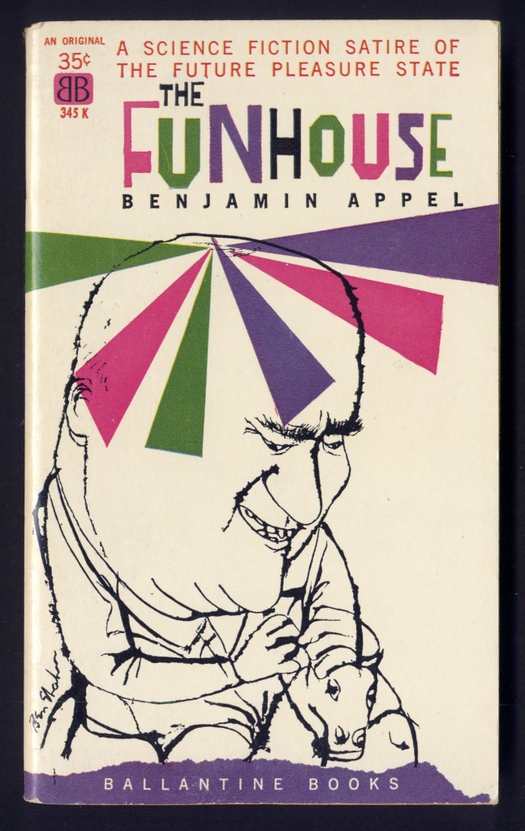

The Funhouse, 1959. Cover illustration by Ben Shahn

On the back of my office door I have a poster produced by product design students at the Royal College of Art in London for their degree show a couple of years ago. It consists of just two sentences: “Everything is becoming science fiction. From the margins of an almost invisible literature has sprung the intact reality of the new century.”

The speaker was the visionary British SF writer J. G. Ballard and the students, participants in a group called Platform 11, cheated a bit. What Ballard actually said, writing in 1971, was “the 20th century,” but no great harm is done because his point is even more relevant today than it was 40 years ago. Everything has become science fiction. In both positive and negative senses, we are living in a version of the future that mid-20th century SF writers dreamed about. The digital world is thrilling. Could there be a more SF consumer product than the iPad? Meanwhile, unrepentant, unrestrained turbo-capitalism speeds us towards dystopian catastrophe.

That leaves science fiction, always a marginal, lowbrow and unfairly underrated genre, in a curious position. Many people, particularly those who never read SF, view it as primarily a literature of prediction, offering fantastic panoramic visions of how life might be in the future. SF’s first great writer, H. G. Wells, was a brilliant predictor and early SF abounds with images of new technology, new vehicles and new forms communication, incredible cities and interplanetary travel.

But another purpose of SF — the task that engaged the late J. G. Ballard — was to probe and understand the present by extrapolating new social, technological and media developments into the near future to see what they tell us about ourselves. This is SF as social criticism rather than as a naively optimistic R&D dept.

In the January issue of Wired (UK), two columnists argue the case for the different kinds of SF. Russell M. Davies hankers after some inspiring future possibilities from writers like William Gibson who have given up on speculation because the complexities of the present make prediction too difficult now. “We want [SF writers] to predict,” writes Davies, “because we want to know what future to build.”

His colleague Warren Ellis takes the extrapolatory view. “Science fiction has other work to do, the work of showing us where we’re really living and who we really are.” The best SF can hope to offer now, he suggests, is a three-minute-warning siren. I’m with Ellis on this one, on balance, though warnings can be as hard to get right as prediction.

“In this biting and satiric novel,” runs the back cover blurb of The Funhouse (1959), “a major American writer looks forward to the day — surely not far away — when machines have taken over all the productive work, the government consists of a battery of Thinking Machines, and the people are turned loose on a perpetual spree . . . this is the America of the Future, a whole country transformed into one gigantic playland.”

So, in Benjamin Appel’s Pleasure State of 2039, the two-hour workday will be optional thanks to the liberating machines. We don’t hear so much about that idea these days.