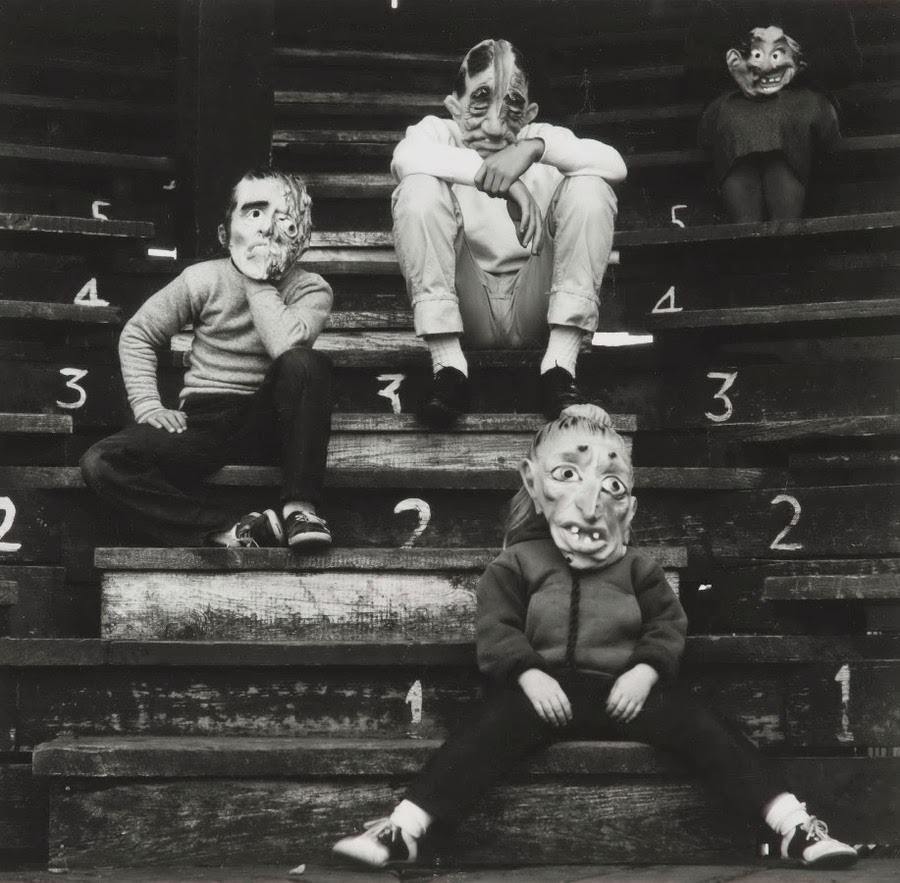

Romance (N.) from Ambrose Bierce #3 by Ralph Eugene Meatyard, 1962

By the time Ralph Eugene Meatyard, an optician and family man from Lexington, Kentucky, shot Romance (N.) from Ambrose Bierce #3, in 1962, his idiosyncratic methods as a photographer were well established. The title refers to an entry about romance, considered as a literary form, in Bierce’s mordant classic The Devil’s Dictionary (1911). “In the novel,” writes Bierce, “the writer’s thought is tethered to probability, as a domestic horse to the hitching-post, but in romance it ranges at will over the entire region of the imagination—free, lawless, immune to bit and rein.”

Meatyard (1925–1972) used ordinary settings—here the rough wooden benches at a local athletic field—for pictures that could be free, lawless, creepy, and uncanny. He found suitable sites, such as derelict houses, by touring his area, and enlisted friends and family members as participants, most often his three children, Michael, Christopher, and Melissa. The figure in the shadows at the top is presumably his wife Madelyn, holding the mask in her lap so it looks like a head on the stumpy body formed by the canopy of her skirt. Meatyard was attracted to Surrealism and his photographs often transform the familiar into something psychologically loaded and unnerving.

Every posed photograph of a person is a performance for the camera, which the subject carries off more or less well. In a successful performance, the face seems to represent the person’s inner essence, though this may be no more than a fiction, an illusion that the photogenic subject knows from experience how to construct. In Meatyard’s picture, an ambiguous jest, if it’s a jest at all, grotesque Halloween masks bought from Woolworths replace the ordinary “mask” of each person’s face. (The mask worn by Melissa reappeared in a famous series titled The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater, where Madelyn Meatyard sports it in every deadpan picture.) Without the family’s faces and expressions to guide us, their body language becomes harder to read, and we start to take cues from the outlandish masks. Is this child bored or dejected? Does that one look skeptical? Do they collectively seem sullen, listless or defiant?

Posed on the rudimentary benches, the family forms an audience—it might even be a jury—for the photographer, whose subjectivity, as the scene’s orchestrator, is perhaps the picture’s ultimate concern. The crudely painted numbers, which suggest a process of classification or grading, stutter uneasily between the sitters. These mask-wearers are manifestly unknowable—just as we are all finally unknowable to each other—and the picture is a hauntingly strange performance of the condition of otherness, inescapable even within the close bonds of a family.

See all Exposure columns