The Smokers’ Room, Frederic Marès Museum

In 2007, while staying in Barcelona, I visited the Frederic Marès Museum located in the Gothic quarter in the heart of the city. I had been to Barcelona several times before, but had somehow overlooked a collection of art and artifacts that is by any standards extraordinary. Marès (1893-1991) was a hugely successful Catalan sculptor with a passion for acquisition that started in boyhood, which you can’t help feeling — the deeper into his world of objects you descend — verged on a polite, socially sanctioned form of mania. By comparison, Warhol’s obsession with stashing away anything and everything, revealed to the world after his death, seems almost junior league. What only 10,000 items, Andy?

“I make sculptures to buy sculpture,” Marès said. These old works of art, including many superb Gothic carvings of the Madonna and Child, the crucifixion and the saints, are the art historical center of the collection. But there is so much more to see. Visiting Barcelona last week to speak at the OFFF conference, I couldn’t resist going back to the museum, which reopened in May after 18 months of renovation.

I particularly wanted to revisit a section now called the Collector’s Cabinet. It encompasses 17 rooms said to contain more than 50,000 items. Four years ago, I lingered in a large hall devoted to all the paraphernalia of smoking, not because I have ever been a smoker (though the culture and imagery of smoking fascinates me) but because this chamber is both the most graphic in content and the most visually overloaded and utterly overwhelming of all the rooms. I took notes during that visit and had planned to write about the Cabinet for Design Observer, but decided my photos weren’t good enough. The latest visit provided an opportunity to take some new pictures and finish the job.

The Smokers’ Room, Frederic Marès Museum

In its sensorial and intellectual effect, the Smokers’ Room is a microcosm of the entire museum. It defeats your powers of perception and understanding. Everything is beautifully displayed in these subdued, elegant, atmospherically lit rooms, but nothing in the Cabinet is labeled: no dates, no confirmation of what the item is, no explanations about its use (presumably this will one day be rectified, a vast curatorial undertaking). As a casual visitor, you can sample the collection, brush its surface, appreciate it in broad outline, marvel at its curatorial sweep, but without dozens of visits you cannot finally know it — it is too vast to know. You cannot even see it all. There is simply too much to see. Many museums have this sense of too-muchness even to the point of redundancy. The Frederic Marès Museum is the most extreme example of this tendency I have seen. Trying and inevitably failing to take it all in, people wander about vaguely, not knowing where to pause and start digging into this prodigious avalanche of things. Any concentration of effort in one place, when there is so much more left to see, seems arbitrary and self-defeating.

The Smokers’ Room, Frederic Marès Museum

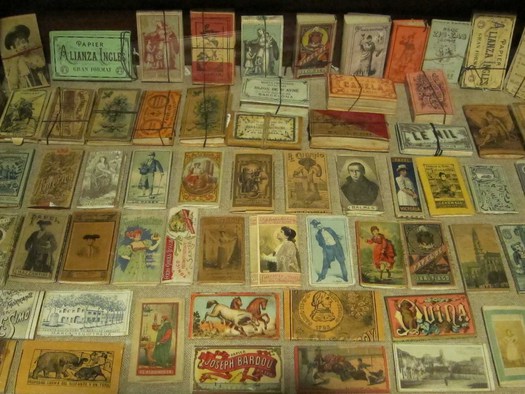

Confronted once again by the impossibility of the task, I decided to retrace my earlier steps, using my notes as a guide. In 2007, I concluded that the only way to make headway was to select at random a section of the Smokers’ Room and give it all my attention until I had really seen it. If this sounds like exaggeration, some figures might help. There are two iron display stands in the room with rotating, double-sided, glass-fronted panels, displaying matchbox labels. Each of the 16 frames contains 83 labels, giving a total of 1,328 images to assimilate in this small section of the room. Similar panels, frames and displays cover the walls.

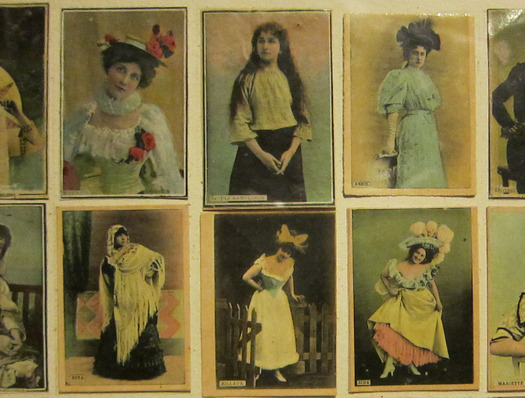

On my earlier visit, I had been looking at matchbox labels with pictures of actresses, opera singers and dancers — forgotten figures such as Liane de Pougy, Rosario Pino, Emma Calvé, Cato Villarose and Lucy Gerard. The names in the corners of the labels are so tiny that it was necessary, as it still is, to press up against the glass to read them. Last time, studying a set of black-and-white portraits, I was peering so closely that it took me a long time to realize that in the neighboring frame, color versions of the same pictures appear in exactly the same positions — how many visitors to the Smokers’ Room ever notice this? In this gloomy corner, perusing details of period clothing, facial expression, or hairstyle in one of these miniature portraits of women who died decades ago, it seemed quite possible that I might be the only visitor ever to have examined the image. It is like singling out a leaf in a tree for close study: most leaves are never looked at by anyone.

The Smokers’ Room, Frederic Marès Museum

The museum invites you to enter its universe of fixation and repay its superabundance with your undivided attention, yet as soon as you give the exhibits more than the usual cursory glance, you feel you are behaving oddly, obsessively, excessively. The more minutely focused you become, as you must to see these objects properly, the more eccentric you will appear. Most people enter the room, absorb the general effect, look briefly at a few items that catch their eye and soon move on to the next room, and the next, while you remain, bestowing unwarranted amounts of attention on ephemera. But if these objects don’t warrant close attention, why are they there? Simply to show that a wealthy man in the grip of a compulsion once went to the extreme length of collecting all this stuff?

The Smokers’ Room, Frederic Marès Museum

And I haven’t even begun to mention the many other attractions in the Collector’s Cabinet, such as the Ladies’ Quarter, the most seductively lit of all the 17 chambers, with its collections of fans, purses, nut crackers, earrings, hair combs, candle extinguishers, perfume bottles, powder boxes and needle cases; or the Gentlemen’s Quarter, with its canes, pocket watches, opera glasses and embroidered wallets — each object type belonging to a sub-collection that could in theory keep on expanding its taxonomical net until it included every known example in the country or the world. For, in the end, that is what Marès’ museum invariably compels you to consider: the unknowably limitless profusion of human-made artifacts (as well as natural forms of creation). Only the mind of God could possibly take account — so we are told — of all these things.

The Smokers’ Room, Frederic Marès Museum

Marès’ irresistible urge to collect seems to have been limited only by what was physically available to buy, or came his way as a donation. He gave his collection to the city of Barcelona in 1946. His legacy is not so much a cabinet of curiosities — the term implied by “Collector’s Cabinet” feels too limited here — as a mind-bending, sense-bedazzling grand palais of artifactual wonders.

Photographs: Rick Poynor