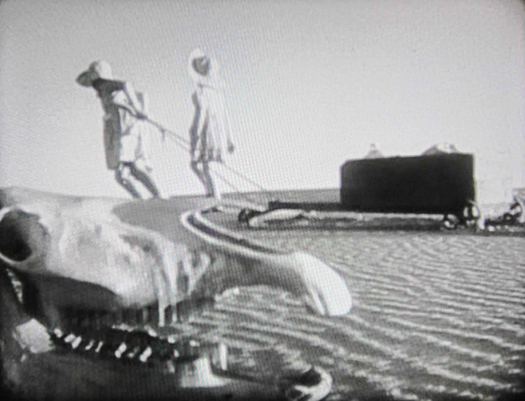

One of the lost girls in The Back of Beyond directed by John Heyer, 1954

A few years ago, talking to the designer Ed Fella, I discovered that we shared an enthusiasm for The Back of Beyond, a remarkably poetic Australian film made in the outback in 1954. It was one of those unexpected moments when you feel like you have encountered a fellow member of a secret club. Best described as a docudrama, The Back of Beyond was highly regarded in its day, winning the Grand Prix at the Venice Film Festival, and it retains a reputation in Australia as one of the country’s finest productions. Elsewhere, few today have seen this masterpiece, which isn’t currently available on DVD in either the US or the UK, though it’s an obvious candidate for release by Criterion or the British Film Institute.

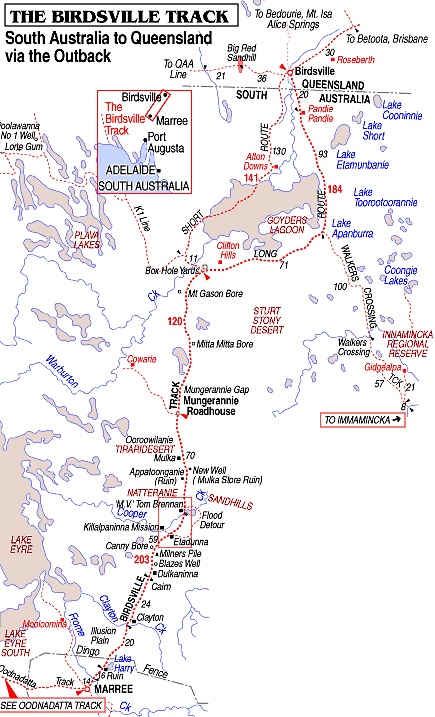

The 66-minute film, directed for the Shell Film Unit by John Heyer, follows the journey of a now legendary mailman, Tom Kruse, along the 350-mile Birdsville Track from Marree in South Australia to Birdsville in Queensland.

Kruse drives a battered old truck loaded with the mail, vital supplies for the sparse settlements along the route, and occasional intrepid passengers. Conditions in the desert are ferociously harsh. First glimpses of the place introduce an alien, sun-blasted, primordial landscape littered with ancient fossils, bones and skulls. Kruse’s mission, every two weeks, is to complete the journey, come what may. He is both a contractor with a job to do and an Australian archetype, an unflappable bushman able to get by despite the sand, heat, flies, snakes and other dangers.

Off the Birdsville Track

Tom Kruse at the wheel of his Leyland Badger truck

Heyer, then head of the Shell Film Unit in Australia, spent three years planning, producing and finishing the film; the shoot took six weeks. Some of the incidents were re-enacted and the script, co-written by Heyer, his wife Janet, and the poet Douglas Stewart, is lyrical and poetic. On the journey, we meet characters such as Dervish Bejah, an Indian camel driver, who fights the desert “by compass and Koran,” and Jack the Dogger, who makes some kind of living killing dingoes. The visual style is a heightened realism that often becomes Surrealism, as when the desiccated carcass of a cow destroyed by an earlier flood hangs in the branches of a tree (two years earlier, the painter Sydney Nolan made photographs of similar sights in the area). Shortly after this, Kruse and his companions relax in an improvised, open-air living room next to a flooded creek, with an armchair, cooking facilities and a dressmaker’s dummy, with which Kruse dances to the music of a gramophone. An Aboriginal stockman stands in an abandoned Christian mission remembering his time there while the camera explores the melancholy ruins like an analytical probe. At best the people are holding their own against a hostile land that might at any time crush their efforts to establish a place in its emptiness, and expel them.

By Cooper Creek

In perhaps the film’s most famous sequence, Heyer tells the cautionary tale of two lost girls, Sally and Roberta, who set off into the desert with a cart, a bottle of water and the family dog after their mother dies. This is a perfectly constructed piece of narrative cinema, heart-rendingly simple images crafted with an elemental power that suggests Heyer could have made great feature films given the chance. There is a quietly horrifying moment when the older girl, coming across their earlier cart tracks, realizes they have been walking in circles. She keeps the terrible truth from her sister. The sequence takes its place in a mythology of children lost in the threatening vastness of the savage Australian interior that stretches from 19th-century landscape painting to Peter Weir’s later film, Picnic at Hanging Rock.

The lost girls

One might wonder what Shell hoped to achieve with such an astonishing film. The Back of Beyond certainly wasn’t advertising in any conventional sense and if the logo at the start were removed there would be nothing to associate it with the company. Heyer’s brief seems to have been to identify Shell strongly with “Australian-ness,” with the aim of capturing “an entire national ethos and its enduring values,” as the Shell Australia website puts it today. The film was shown widely in Australia and estimates suggest that as many as 750,000 saw it in the first year of release. Its impact was such that in 1968 the British Film Institute published a study guide. The Back of Beyond isn’t on YouTube, but Australian Screen has three terrific clips. In 2004, it was released on DVD in Australia in a 50th anniversary edition, along with Last Mail from Birdsville, a documentary about Tom Kruse. This set is still available in a Region 4 version.