Trail Drive and Pavilion, Montrose, Scotland, date unknown. Valentine’s Series

The grouchy existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre famously declared, “Hell is other people.” If JPS had been around today, he might have felt obliged to revise that axiom. In the age of the upload, when no personal snap is too inconsequential to post, we confront the stark possibility that hell just might be other people’s photographs. We have gone from politely tolerating our friends and relatives’ holiday snaps when they insisted on showing them to being publicly inundated with millions of images of no interest to anyone other than the participants. As the Dutch ad man, photo collector and curator Erik Kessels puts it, we are “drowning in pictures of the experiences of others.”

Kessels makes the point more overwhelmingly than it has probably ever been made before in an installation now running at the Foam photography gallery in Amsterdam. He has printed out every single image uploaded to Flickr in a 24-hour period. Hundreds of thousands of pictures surge across the gallery floor and wash up against the walls in great unrestrained swells of image production. Some people reacted to the spectacle by earnestly worrying about possible copyright violations; others wagged a stern finger about the trees. But as a jaw-dropping visualization of the mind-defeating galleries of imagery accumulating in our potentially infinite digital image-bank, I’m inclined to feel it was worth going to such extreme illustrative lengths at least once, and I’m sorry I won’t be able to see it for myself at Foam.

Still from Les Carabiniers, directed by Jean-Luc Godard, 1963 (via Tom Sutpen)

The pictures of the installation made me think of the scene at the end of Godard’s Les Carabiniers where two soldiers return to their wives from a war with a suitcase full of postcards — the plunder they have gathered during the campaign. Postcards were the first great wave of internationally circulated standalone imagery. The soldiers’ cards are bundled up by subject and they slap them down on the table, calling out a litany of names: famous buildings, methods of transport, natural wonders, great department stores, animals, female beauties. It’s a brilliant encapsulation of what Susan Sontag in On Photography called the self-devouring nature of the photographic project: “As we make images and consume them, we need still more images; and still more.” There are so many images, even more than the case appeared to contain, that the soldiers and their wives eventually start throwing them around the room. (It’s a long sequence and starts at 4:40.)

By chance, at the weekend, I acquired a bundle of old postcards, which belonged to an elderly gentleman who died recently. I am showing five of them here. I collect postcards if they speak to me as images, though I’m not a completist out to acquire whole sets, or multiple copies of a particular genre of picture. I do find I’m repeatedly drawn to the kind of deadpan topographic scene that the photographer Martin Parr labeled “boring postcards,” although these ostensibly banal views of ordinary places as they used to be are only tedious until the moment you look at them closely: then they can become fascinating.

Dorward Road, Montrose, Scotland, date unknown. Excelsior Series

Queen’s Avenue, Aldershot, England, date unknown. F. Frith and Co.

The Mall, Montrose, Scotland, date unknown. Excelsior Series

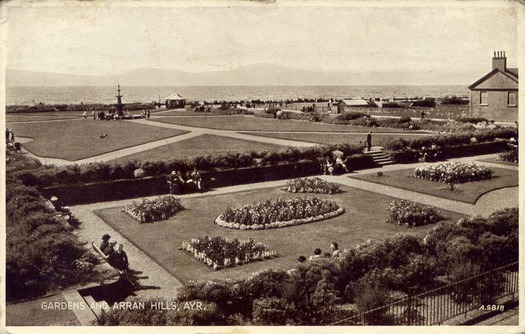

Gardens and Arran Hills, Ayr, Scotland, franked on 30 May 1942. Valentine’s Phototype Series

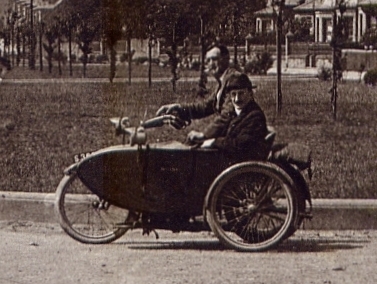

The five scenes from Britain in the first half of the 20th century are all notable for the depth of the picture space. The eye glides over the subject to the back of the image where the sky meets the land; in two pictures, sharp lines of perspective converge on a vanishing point. The streets aren’t particularly broad but the scarcity of traffic makes them seem peculiarly open and spacious. These mainly monochromatic vistas feel empty, becalmed; there is great stillness and even stasis in the pictures. Are the motorbike and sidecar actually moving? A biplane hangs in the air like a toy not far above the ground. People stop to watch the photographer who has set up his camera to observe them, as though they are waiting for something to happen. The photographer’s invisible presence has become the only mildly noteworthy event recorded in the picture.

Nevertheless, the captions are absolutely specific about the scene. This is not just any old street — it is Dorward Road in Montrose (Scotland), viewed from the Gates. Who would have cared, apart from people in the area and perhaps any visitors who wanted a memento? They would write on the back and mail the card to someone who lived in a similar street that might have been the subject of its own uneventful postcard. To have sent a banal card that had nothing to do with you would have been to betray a prematurely Parr-like sense of pictorial irony.

The individuals accidentally captured in these pictures are so tiny within the image area that it would be easy to treat them only as part of the scenery. Peer closer, though, enlarge them, and these microscopic presences begin to come alive. The motorcyclist and his moustache-wearing passenger are turning their heads to look at us intently.

In the gardens at Ayr, a young man swivels on the bench. We can’t see what had attracted his attention in this passing moment and we will never be able to find out, though he could still be alive since the postcard was sent in 1942.

Most mysterious are the two women beside the lamp post, walking away from us along the Mall; or could the shorter one — look at the slight bend in her arm — be heading our way? Perhaps both of them are. These chastely attired pedestrians of long ago remain only as transient blurs, smudges in time, ghostly sepia traces caused by prolonged exposure, in a tarnished picture on an ephemeral postcard that no one, including the card’s deceased owner, is likely to have looked at for decades, assuming that other copies even survive — until now.

This takes us into the same melancholy territory as my previous posts about the hilltop cemetery in Nice and the Frederic Marès Museum in Barcelona. The world is deluged with objects and images intended to record and remind us of people and places and, once their immediate moment has passed and the emotional connection has been severed, most are ignored. My choices of postcard to write about here might seem whimsical or arbitrary. They are, but it could scarcely be otherwise. At least they are conscious choices. We make meaning by selecting and discarding — by editing. The more images we collectively over-produce, the more ruthless we need to be as individual viewers in bestowing our precious attention only on things that matter to us.

The unceasing production of personal photographs provides consolation for the ego, yet it is also a delusion: most of these images are hurtling toward oblivion. Handily we have a limitless electronic warehouse to store our visual dead letters in now. So here, recovered from the universe of paper, and reversing the process seen in Erik Kessels’ installation, are five more forgotten photos to file away for the future on the invisible shelves.

See also:

Surrealism in the Pre-School Years