Barbara Shawcroft, Arizona Inner Space, 1971

“You know, you’re really nobody in Los Angeles unless you live in a house with a really big door,”—Steve Martin

Oddly, my life recently intersected with the big door issue. A friend directed me to the sale of a set of doors designed for Forms and Surfaces in 1973. They are magnificent examples of the post-war west coast craft and style movement. Unfortunately, my front door is a standard size and a 6-foot wide set of doors will not fit. I also can’t spend the equivalent of a small house on two doors.

Forms and Surfaces, Bronze Doors, 1973

The West Coast Craft and Style movement led to the publication of a series of exhibitions and thirteen books, California Design. The content is not a collection of Santa Claus figures made with felt and a toilet paper roll. It represented a movement that started after World War II when artists and designers, working in California, explored new materials and techniques. Taking the concepts of modernism and optimism, artists crafted functional objects, furniture, pottery, and textiles using natural materials. Tupperware, pastel-colored plastic radios, faux wood chairs, and Naugahyde spoke to technologies and materials developed during the war. The craft movement turned toward nature as a response to the industrial mechanization of production and proliferation of new synthetic materials.

The environment and history of California also informed the work. Natural materials alluded to the redwood forests, Sierra Nevada mountains, and endless beaches. There was a historical connection to the Arts and Crafts movement and Greene and Greene’s architecture using handmade and unique doors, cabinets, and dinnerware. The environment and history inspired the colors. Orange came from the California Poppy and oranges grown since the early mission period. The 1859 Gold Rush inspired ochre and gold. And the natural world created palettes of brown, rust, avocado, and burnt red.

LEFT: John Marko, 1962. RIGHT: Architectural Pottery, 1965.

LEFT: Jean Ray Laury, Scarlet Garden, 1962. RIGHT: Evelyn and Jerome Ackerman, 1971

Jackson and Ellamarie Wooley, 1962

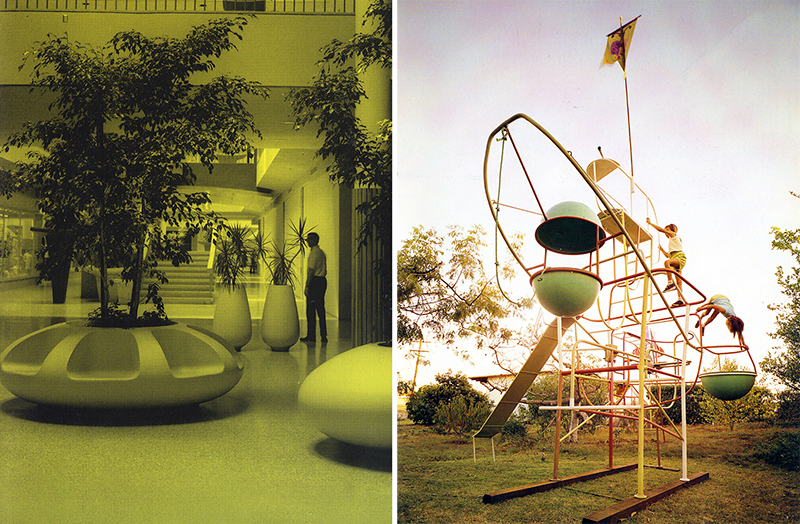

The movement evolved, and by the 1970s, artists and designers created increasingly fanciful and provocative work led by the counter-culture attitude. Barbara Shawcroft’s Arizona Inner Space (1971) is, perhaps, the most miraculous house made with textiles ever. Evelyn Ackerman’s Animal Block Series (1971) is a musical narrative. Elsie Crawford and Douglas Deeds addressed the public sphere and urban experience with experimental fiberglass benches and seating.

The sleek aesthetic of the late 1970s and appropriation of the synthetic in the 1980s drove the movement to the backburner. Many California art and design schools have the myth of a kiln that once serviced a ceramics major. In the past decade, the artifacts represented in the California Design books have found homes in high-end stores that previously focused on mid-century furniture and art. The technological and easily disposable manufactured world today has rekindled the drive to use natural materials and actual human hands to create. I may not be able to build Saarinen Womb Chair, but I can learn to macramé a hanging house.

To read issue 11 of California Design, click here.

LEFT: Elsie Crawford, Architectural Fiberglass, 1968. RIGHT: Ruth and Svetozar Radakovitch, 1965.

Douglas Deeds, Architectural Fiberglass, 1968.